By Daniel de la Calle

I really wanted to visit some of the cerrado National Parks during the screening tour in Brazil in March and April, but it was not possible. The dates did not leave a window of time big enough to “escape” to the countryside between each city. I thought it would be a long time before I had another chance to fly to South America and fulfill this desire, but I was so wrong. Not even a week after my return to the US the production company received an invitation to take part in FICA again, the film festival that A Sea Change won last year, this time as part of a series of films to be screened for school children from the State of Goias. I wrote to the organizers and suggested we did a little more than just show the film; I wanted to go down there and meet them, talk to them about ocean acidification and do a simple chemistry experiment to exemplify what an acidic ocean does to shell forming organisms. They liked the idea and so it was that, barely a month after leaving Río, that I was heading South again on an early June night.

My expectations were very high, but even so the cerrado did not disappoint me at all. It is wild, it is pure, it is extremely beautiful, bizarre and surprising. Animals, birds and plants seem to have come out of a Dr. Seuss book. The giant anteater with its long hairs, nose and tongue, the toucans and parrots, the palms, sticky plants, fragrant leaves, thorny bushes. Everything was new and unique to me. And for good reason, forty some percent of all I saw was endemic; this ecosystem is so important that, in a country like Brazil that holds the Amazon jungle, the cerrado still counts for over thirty percent of all the biodiversity in the nation. The big threat to these gorgeous savannas and bushy areas are the dry season fires and the clearings done for soy and cattle farming. Fires are strictly forbidden, but one would think that they are actually encouraged. Everywhere I went people were burning grass and low bush by the side of the road, in farms, in the forests. This practice could not be more dangerous. The dry season lasts half of the year and usually, once a fire gets out of control during these months there is absolutely no way people will manage to stop it. Some plants have adapted to fires and have the most ingenious ways of “escaping” or surviving fires, but many others and all animals caught in it perish and take an awful long time to repopulate the area because conditions in the cerrado are extreme and hard (six months of rain, six months of “seca”, the dry season). I came to realize that legislation is not going to do much to discourage “winter” burnings, that the only way to dissuade Brazilians from eradicating the mato is to educate them, to teach them to love this magnificent environment that they take for granted and to teach them about the consequences of fires. The cerrado, as I have already mentioned on previous posts in this blog, is the most threatened environment in all Brazil, way above the Amazonia.

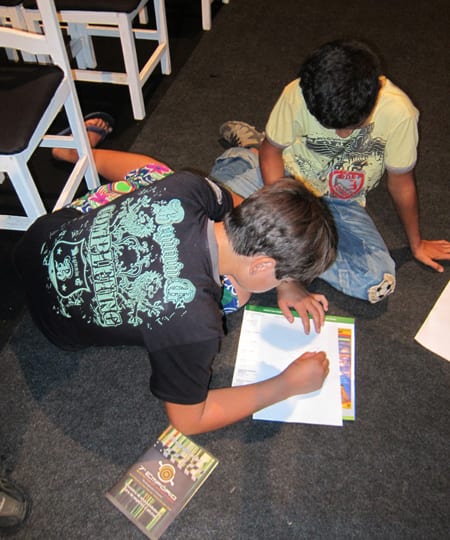

Education has always looked to me like the only true key to hope and change in all matters, including the way we treat the planet, so I was elated to have the opportunity to show the film to 500 kids and talk to them for a couple minutes. There were children and teenagers of all ages, from 5 to 17. They were loud, they were having fun, they were nervous. The room was huge, it is the same one used for the Festival’s closing ceremony, but in less than five minutes it filled up. They were making so much noise during the opening scene that you could not hear a thing. How loud were they? About this LOUD

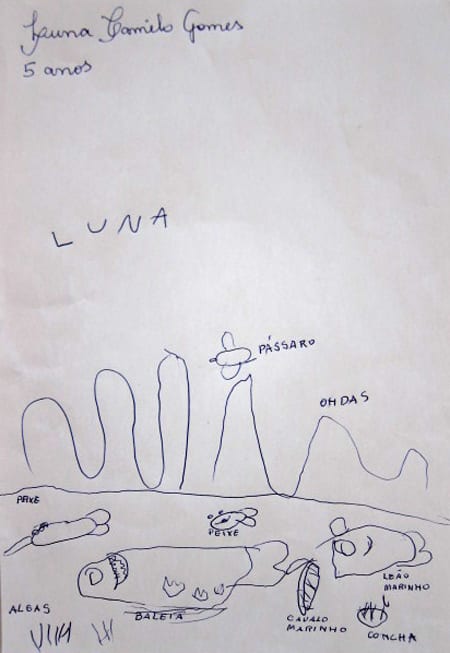

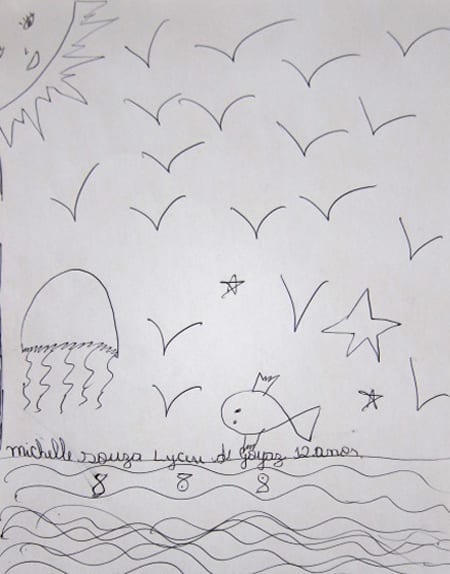

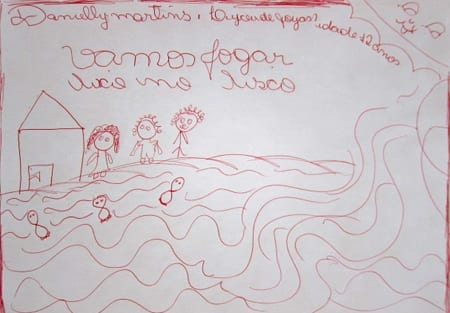

Unfortunately, some of them had to leave before it was over because they had come by bus from distant towns and villages and had to begin their way back, but a good number of them stayed until the end. I had promised to ask a few simple questions about the film and reward those that knew the answers with some of our merchandise, so the kids (and quite many adults) were pretty excited. I also asked the younger children to please make a drawing with whatever part of the documentary or animal shown in it that they liked and we quickly assembled an informal jury to reward the best five or six with a Niijii Films baseball cap as well. I wished I had brought 100 and not just a handful, it was heartbreaking to see some of those disappointed eyes. The most difficult question I asked seemed to be to name in an understandable way the little shell with wings that appears several times throughout the film. The word “pteropod” is not the easiest one to pronounce for a 12 year old Brazilian kid; some pretty comical and unintelligible replies, formed mostly by the urge to own a baseball cap, came out of those mouths. Finally, I told them all to come close to the stage and hold two cups in their hands, one filled with water and one filled with vinegar. Then we gave each one of them several pieces of chalk while I explained that they should imagine the acidic ocean being the cup of vinegar and the shell forming organism being the pieces of chalk. There was some initial confusion because the chalk was bubbling in the water as well as in the vinegar, but once the air inside it had come out they could see the vinegar getting all murky and the chalk stick slowly dissolving. I knew all this was quite a stretch for a little girl that has never seen the ocean or eaten shellfish and is at the beginning of her school years, but I think they got the essence of the message and both students and teachers were absolutely fascinated by the chemistry behind the terrible problem of ocean acidification. I believe and hope the experiment is going to be replicated in classrooms during the next few months.

Here are a few of the drawings I took with me, all of them winners of the Niijii Films cap that is now often seen around the State of Goias: