By Daniel de la Calle

After Puerto Montt, the second half of the series of screenings in Chile unfolded at universities in Santiago and Valparaíso. Although they shared the name, “Universidad Católica”, there was no connection between the two. We were in Santiago thanks to an invitation by Professor José M. Farina, showing the film in their downtown campus, a few minutes away from sadly famous since 1973 Palacio de la Moneda. Had a most interesting conversation with Professor Farina where he let me know that Ocean Acidification is not one of the top priorities or concerns amongst the small oceanography and marine biology community in Chile and that, needless to say, the phenomenon is completely unknown by the general public. Things like climate change, pollution from salmon farms, green tides, the niño/niña phenomenon or water hypoxia rank much higher in the agenda. I knew nothing about water hypoxia and was fascinated and terrified by the description. It seems that along the Chilean coast there is a not too deep layer of water depleted of oxygen, a dead zone for marine fauna. Sometimes, for reasons they are studying, it slowly raises up to the surface like an silky vail of death and kills all life it touches.

At the screening the attending students had organized an informal pre-screening informal gathering with coffee and pastries, so we got to meet and chat for a few minutes before, which was a great idea because I felt it broke the ice for later. We had a small technical problem that turned images rather green (green tide!), but they all watched with great interest nonetheless and our conversation and q&a afterwards lasted longer than the film itself. There were members of the Ecology, Biology, Oceanography and Environmental Sciences Departments and I learned a lot from them while also trying to emphasize the need society has of their work and our desire to bring changes to the world. Enthusiasm run high and I was promised screenings at schools around Santiago to educate kids about Ocean Acidification and the beginning by one of the students of a small college newspaper about marine science. I do not really know if any of it will actually happen, these were promises made in the heat of the moment, but their feelings and passion were so sincere that they alone would have made completely worth our efforts to fly to Chile this month.

The next morning I was on a bus to Valparaíso for our final showing in the country. While in Santiago I had stayed a block away from Pablo Neruda’s house “La Chascona”, the one ransacked by Pinochet’s hyenas, and upon my arrival into “Valpo” I discovered my accommodation was also five minutes from “La Sebastiana”, his home sitting on a hill.  Fresco detail in La Chascona

Fresco detail in La Chascona

Neruda loved the oceans, he obsessed with ships and anything smelling of salt and iodine, evoking sea travel. In the houses he built he always tried to replicate the interior of sailboats: the dining rooms are long, narrow, with low ceilings, the wooden floors crack, gently rocking below your feet, certain windows are portholes and most of furniture came from sea vessels, like the gorgeous bar where he entertained and prepared cocktails for friends, the office desk on the last floor that had once belonged to the captain of a merchant ship or the nightstands by the large bed. He amassed a vast collection of shells and several majestic figureheads. Like a beachcomber, he was a collector of everything and anything, constantly thirsty for beauty and uniqueness. The house in Valparaíso is in the perfect location to encompass the whole bay. Beside one of its ample windows he placed his favorite armchair; it is there he wrote many of his poems, always using green ink, perching over the harbor, getting up every now and then to look into his spyglass at distant ships. But, surprisingly, Pablo Neruda was also utterly terrified of being aboard a ship and in the few occasions he did he became terribly seasick. A perfect epitome of the Chilean man, enveloped in the unequivocal presence of the Pacific Ocean, swirling in a game of love, fascination, dependence and fear, but a distant stranger to it all the same.

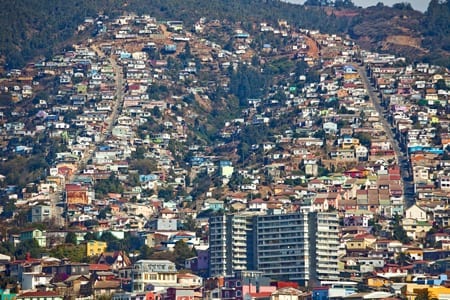

The pretty theater at the Universidad Católica de Valparaíso was full on both floors with kids and young adults, most in school uniforms. The screening went well, colors looked the way they should and our conversation at the end was extremely lengthy once again. I might talk too much. Professors complained about the lack of interest from Chilean students in science, marine science more in particular, and those young men and women asked some very good questions. Several got carried away like in Santiago and offered to spread the word on Ocean Acidification in schools and amongst friends. All that time we were less than a hundred meters from the water, but a road and a fence separated the bay from us, making it invisible. Maybe that is why most of the attendants had never even seen Valparaíso and the seals living in the harbor from the water.  Ms. Marina Vivar, from the local Natural History Museum purchased a copy of the film and asked if it would be ok to have it loop-playing in their newly renovated facilities. Another lady, the head of science college programs in the region, purchased one as well and proposed further screenings at the university and to leave the documentary also available in the video library. I was invited to lunch (fish soup, finally) by organizing Professor Sergio Palma, and walked from there to the harbor, where old fishing boats are now used to take tourists around the huge dock cranes, through the shipyard, the harems of seals around the blubbery male and the frightening gray muscle of the chilean navy, to the open view of tutti frutti Valparaíso, the city that draws itself on walls and doors, always facing the sea, seldom in it.

Ms. Marina Vivar, from the local Natural History Museum purchased a copy of the film and asked if it would be ok to have it loop-playing in their newly renovated facilities. Another lady, the head of science college programs in the region, purchased one as well and proposed further screenings at the university and to leave the documentary also available in the video library. I was invited to lunch (fish soup, finally) by organizing Professor Sergio Palma, and walked from there to the harbor, where old fishing boats are now used to take tourists around the huge dock cranes, through the shipyard, the harems of seals around the blubbery male and the frightening gray muscle of the chilean navy, to the open view of tutti frutti Valparaíso, the city that draws itself on walls and doors, always facing the sea, seldom in it.