By Daniel de la Calle

These past Friday and Saturday we had two screenings of A Sea Change in Cartagena de Indias.

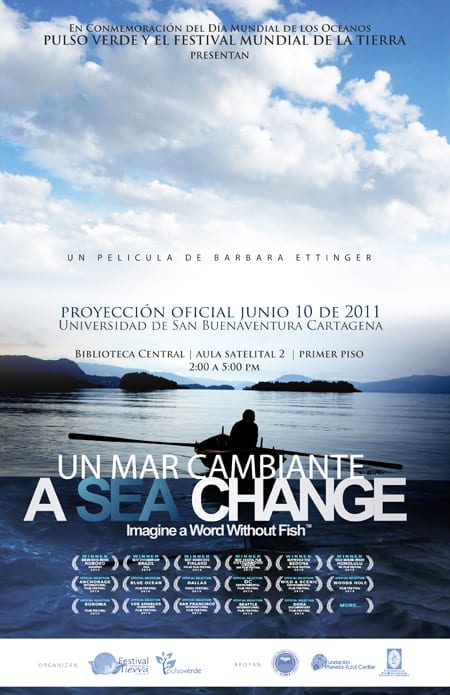

The first one was organized at the University of San Buenaventura by the faculty staff and a local environmental organization called Pulso Verde. Most of the audience was made of college students and a large group of young boys and girls in school uniforms (invited by Pulso Verde, I assume). A couple journalists and some of the faculty staff attended the event as well, so we had a pretty diverse set of people. Here is the nice invitation card and poster they sent out to advertise it:

The Saturday screening was at one of the many hotels in Cartagena de Indias. On this occasion a smaller group of engineers, biologists and environmentalists gathered at one of the rooms of the Caribe Hotel to conclude a course on environmental management with the screening of our film. How nice is that! All the attendees knew about Ocean Acidification, which meant that the debate was a bit more technical and also concerned all the (many) ecological problems the area around Cartagena de Indias is facing, from coral bleaching to acidification, from contamination of the Magdalena river to the numerous damaged mangrove swamps and lagoons that surround this photogenic historic town from Spanish colonial times.

The old historic sector with its defensive wall

At the end of it I had a long conversation with a man called Miguel Rozo, a Colombian diver that has seen the decay of the Rosario National Park coral reefs over the past 35 years. Miguel loves the seas, spends every single day either sailing, diving to examine damaged reefs with scientists, inspecting boats to make sure they comply with environmental regulations and free diving. He told me he is just a novice at this sport and can only hold his breath for four and a half minutes at 130 feet of depth, nothing compared to the 18 minutes some human amphibians do these days. Miguel is very critical with the status quo and with society, and in his critique he includes the many “office environmentalists”. I think he is right. He gave up his car 8 years ago, unplugged his life except for a computer, a cell phone and the cooking stove and lives with no other appliances or air conditioning, no fridge, no nothing in a 14th floor apartment (it gets a good cross breeze to keep coolish, since nothing seems to be cool in this Caribbean steam bath). He only uses public transportation or his bicycle.

We hang out for a while, went to the supermarket to get his dinner and then took the bus together, where he reflected: “All those people tonight at the screening talked and talked about what the government and industries should do, about the level of environmental devastation on the coast. I bear witness to that, tourists are taken to the few nice dive spots that are left, to see the remaining corals, while everything around it is dead or dying; nobody wants to see the dead corals, the underwater deserts. 40% of what was here 35 years ago is gone and gone forever. But those people tonight are the environmentalists, they fill their mouths with big words and great proposals, theorize and show their concern for an hour to then drive away in their huge cars, one on each. I know them all personally.

I went from theory to practice many years ago. It is not only possible to live consuming a tenth of what we do, but it actually feels better. People tell me I look good, I look so relaxed. And I feel good, I do not feel 58, I have the same energy as a 20 year old, with no dark clouds above my head or health issues. I take the bus everywhere, share the carbon expense, look at the beautiful women, talk to whoever is beside me.” Sure enough, as if rehearsed, a minute later an exuberant black woman got on the bus and greeted him: “Miguel, what a delight to see you! You look deliciously gorgeous”.

The next day I joined an organized trip (I promise never to do that again) to the Islas del Rosario and Playa Blanca. The experience was terribly depressing, I kept looking for understanding, empathetic eyes from my 25 tourist companions throughout the day. We sped along a coastline mostly made of mangroves, shanties, a few tiny sandy areas and lots and lots of plastic and debris everywhere.

After an half hour we made a stop in front of a local community of fishing boats and houses made of every possible materials. A fortification from Spanish colonial times lay ahead while our guide went through a brief historical account of its defensive value when a bunch of local kids joined us on canoes. The tour guide abruptly wrapped the peppy talk of pirates, thrifty underwater chains to block incursions on the bay, cannonballs and the smell of gunpowder and exclaimed: “These here, my friends, are our local sharks. I live right here, I know them all by name. These modern sharks are tan and fast, but do not fear, they do not eat people any more. If you throw a few coins they will fight each other to retrieve them from the bottom.” A Spanish man who had expressed serious doubts about the underwater chain as a means of stopping pirate vessels felt he needed to at the very least confirm this last statement and produced the equivalent of 10 cents that he threw ten feet away from the kids, in the water. They splashed and stroked towards it and a millisecond later one of them resurfaced with a smiling face. “More!” Beautiful kids, one of them resembled Barak Obama.

Then we continued on our fast boat ride for a half hour to the Islas del Rosario, twenty some private islands in a National Park (go figure) and our guide, named “Chocolate”, pointed from the distance to each one while enumerating who the lucky owners were: all national celebrities I had never heard of and the usual presidential holiday residence each country reserves for its dignitaries. We were offered the possibility of doing some snorkeling on the reef and so I rented goggles and a tube and anxiously dove to “see in person what you only get to watch on tv, the beautiful corals and rainbow colored fish”, as Chocolate put it. As I looked down into the water I felt as if Miguel was back beside me, looking at a huge cemetery of coral skeletons and grayness, with drifting parrotfish pecking here and there, pointing at the healthy corals scattered every 50 yards, sad little islands of green, yellow and red surrounded by millions of fragments of broken and long gone polyp bones, surely laughing at my pathetic apnea-diving abilities.

One of the Rosario Islands

Although I have been a scuba diver for 15 years I have never seen a lush coral reef, never been to an area like this where that was possible, so my disappointment was double: the selfish sadness of being deprived of a long awaited experience and the profound sorrow of being somewhere that had obviously once been lush and was now insultingly barren.

I feel as if I had to extract some conclusion, an opinion to wrap the text up, but I have nothing new to mention, nothing I have not written about on previous posts about previous trips, only the urge for things to change, soon. Too late is now.